He’s a talent in both regards, even if his skill set is a time capsule of a bygone era, and the movie doesn’t ask much more from him than to wait his turn until it’s time to pull his string to perform another song. Like a wind-up toy idly waiting on the shelf for its opportunity to entertain, Vanilla Ice mostly exists as a fascinating image, a collection of 90s fashion quirks & excellent bone structure that only comes alive when he’s prompted to do the one thing he was built for: sing & dance. He is, however, in his own strange way, a beautiful specimen, an object that can be easily commodified. When asked to deliver raw machismo in lines like, “Words of wisdom: drop that zero and get with the hero,” he mumbles his way through the readings as if he were rehearsing them for the first time. Unlike a young Marlon Brando, Vanilla Ice is not exactly oozing with potent sexuality & onscreen charisma. While waiting for one of his buddies’ motorcycles to be repaired at a Pee-wee’s Playhouse style garage described by the soundtrack to be a literal Limbo, Ice’s protagonist, Johnny, strikes up a budding romance with the Girl Next Door and gets blamed for a string of local crimes he had nothing to do with based solely on his outlandish appearance. His big city looks (including a leather jacket that exclaims things like “SEX!” & “YEP!” in gigantic block letters and the loudest pairs of pants this side of MC Hammer), flashy motorcycle antics, and massive overdose of hip hop flavor make him & his crew (a conspicuously black entourage that provides him visual street cred among an endless sea of white faces) out to be a target for wild accusations in the small town they unintentionally invade. Structured as a “rap-oriented” remake of the early Marlon Brando classic The Wild One, Cool as Ice finds its titular star and “Ice Ice Baby” singer stranded in a small town in Everywhere, America. What’s most surprising about Cool as Ice and what makes it a memorable watch, though, is how well it fulfills cinema’s other defining function: art.

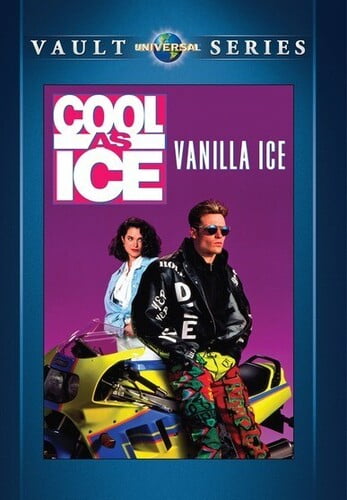

The Vanilla Ice vehicle Cool as Ice, produced at the heights of the white boy rapper’s marketability as a flash-in-the-pan novelty, is one such film, a nakedly honest admission to its own nature as a cynical cash grab.

VANILLA ICE COOL AS ICE MAC

Titles like Space Jam (where the cash-in conscious brand mashup of Looney Tunes & Michael Jordan™ are injected with a wealth of unwarranted, but marketable 90s Attitude) and Mac & Me (where E.T. was shamelessly ripped off to promote a wide range of Coca-Cola & McDonalds products) make for an absurdist, deliriously silly confession of guilt where filmmaking is exposed as the compromised art form that it truly is. What’s always fascinating to me is when that illusion completely breaks down and the “art” of cinema is nakedly exposed as a simultaneously commercial enterprise. They’re not supposed to show their hand while doing so, however, and most audiences prefer to maintain the illusion that their entertainment was produced solely to tell a good story or provide a good time or achieve some kind of transcendent artistic ambition, not to make a quick buck. As Corman points out, not every filmmaker is a Bergman or a Fellini, so the main goal of most films produced in the annual cinematic cycle is to make enough money so that producers can, in turn, make more movies the next go-round. Something that’s especially interesting to me about cinema’s nature as a “compromised” art form is that it’s more or less required to mask the fact that it’s partially a business, hiding its desperate need for profit from its potential customers.

VANILLA ICE COOL AS ICE FULL

It’s even more insightful to me than Roger Ebert’s often-quoted pearl of wisdom about how the movies are “a machine that generates empathy,” because it better takes in the full spectrum of film as both a force for good and a force for commerce. I return to that Corman quote more often than any other summation of what cinema signifies & achieves as an artform. And I do believe to be successful over the long run, unless you’re a Frederico Fellini or an Ingmar Bergman or a true genius in filmmaking, you have to understand that you’re working in both an art and a business.” – Roger Corman They are a compromised art form, and we live in a somewhat compromised time. But another reason that they’re the preeminent art form is that they’re part art and part business. And I think the main reason is they’re an art form of movement, as opposed to the static art forms of previous times. This month Brandon made Boomer, Britnee, and Alli watch Cool as Ice (1991).īrandon: “I do believe motion pictures are the significant art form of their time. Every month one of us makes the rest of the crew watch a movie they’ve never seen before & we discuss it afterwards.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)